Tolpuddle Martyrs.

The Victims of Wiggery 1834

Dorset Agricultural Workers 1830’s

The background behind the transportation of six farm labourers to the penal colony in Australia and Tasmania was based on the fragmentation of social cohesion between the Dorset landowner and the labourer in the 1830’s. A major landowner was James Frampton, Lord of the Manor of Morton House, Justice of the Peace, High Sheriff of Dorset and magistrate. An extract from a diary written by Mary Frampton, James Frampton’s sister provides a very good insight. In November and December 1830, Mary speaks of riots and uprisings by large groups of men demanding higher wages and bent on destroying the labour-saving threshing machines that were threatening their jobs. By early December, the windows and doors of Moreton House were boarded up and Dorset Militia soldiers stood guard. From Mary Frampton diary:

…On 30 November 1830, James Frampton joined 150 farmers (all appointed special constables) to confront a rising by villagers at Winfrith, Wool and Lulworth. Mary continues: ‘The mob, urged on from behind hedges etc by women and children, advanced rather respectfully, and with their hats in their hands, to demand increase of wages, but would not listen to the request that they would disperse. The Riot Act was read. They still urged forwards, and came up close to Mr Frampton’s horse. Frampton collared one man, but he escaped by slipping out of his smock-frock. As news arrived that another ‘mob’ was advancing from Lulworth, three men were arrested and committed to Dorchester Gaol. When James Frampton and his son, Henry, arrived back at Moreton, they described the mob as ‘being in general very fine-looking young men and particularly well dressed, as if they had put on their best clothes for the occasion… 24

On Wednesday 19 March 1834 the six farm labourers were told by the judge presiding at Dorchester Assizes court that they had withdrawn themselves from the recognition of the law and kept their conduct private and secret from the rest of the world. I therefore state that you and each of you be transported to such places beyond the seas as His Majesty’s Council in their discretion shall see fit for the term of seven years.

The first of the six Tolpuddle Martyrs to return was George Loveless who returned to London on the 13 June 1837, he was later encouraged by George Hartwell the secretary of the Central London to Dorchester Committee to write and publish a pamphlet describing the story of how and why the Friendly Society of Agricultural Labourers was born, his arrest with five others, their confinement in prison, the scandalous perversion of the law at their sham trial followed by the horrors of transportation and life in a penal colony on the other side of the world. During their period of incarceration the Martyrs families were not supported by the church or the local farmers and left to starve, but they had been supported by this committee and by July 1837, from funds collected from other unions, there was £600 still in hand with royalties from the pamphlet to arrive.

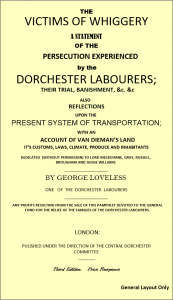

The Title Page of this pamphlet was:

The Victims of Whiggery

A statement of the Persecution Experienced by the Dorchester Labourer; with a Report of the Trial and also a Description of Van Diemen’s Land and Reflections Upon a System of Transportation and dedicated (without permission) to Lord Melbourne, Gray, Russell, Brougham and Judge Williams.

When Loveless had completed the pamphlet it was published and sold for four pennies a copy on the 4 September 1837. By January 1838 it had sold over 12,000 copies in three separate editions. Advertisements promoting the pamphlet appeared in regional newspapers stated that all profits would resulting from the sale of this pamphlet will be devoted to the general fund for the relief of the families of the Dorchester Labourers.

The following text describes why the Friendly Society of Agricultural Labourers was born, his arrest with five others, their confinement in prison and the scandalous perversion of the law at their sham trial followed by the horrors of transportation and life in a penal colony on the other side of the world 23.

Creation of the Friendly Society

Politicians and the aristocracy loathed the trade unions and their members were considered trouble makers out to exploit employers and threaten strikes if their demands were not met. It was illegal before 1824 but they still existed in London, Manchester and Birmingham, but they were subject to severe repression.

It was George’s younger brother, Robert, a Flax Dresser who lived in London’s Marylebone who provided his brothers George and James with details of how to form the Tolpuddle union branch of the Grand National Consolidated Trade Union, this union had a membership of around half a million, in 1834. George wrote a letter in early October 1833 to Robert Owen, the union founder, describing the population of Tolpuddle, the tenant farmers lease payments to the landlord and outlined how the wages of Tolpuddle’s farm labourers had been cut from ten shilling (50p) to seven shillings – with a further threat to reduce it to six shillings.

In October 1833, the inaugural meeting was held in Thomas Standfields cottage, forty farm workers turned up, some were from Bere Regis and one was a Wesleyan Methodist lay preacher similar to George and James Loveless. There were two strangers from London who were representatives from the Grand National Consolidated Trade Union, they addressed to members and explained that the government had given sanctions to the unions, they had been legal since July 1833 and thousands of men were now members. The society would ask each member to pay a one shilling joining fee – a day’s pay and following the initiation ceremony into the society, a penny a week afterwards. They would all swear allegiance to the union. A few days later each new society member received an unsigned letter stating:

Brethren, this will inform you there is a possibility of getting a just remuneration for your labour without any violation of the law or bring your person into trouble. If men are willing to accept of what is offered, then labouring men may get two shillings as easy as they now get one shilling (5p) only per day.

A few days before Christmas 1833 members arrived at the meeting room in Standfield’s cottage to swear in more new members. Amongst them were two spies from James Frampton, John Lock – son of Frampton’s head gardener, and Edward Legg a farm labourer from a nearby farm in Aftpiddle; they had been brought to the meeting by James Brine. The strangers proceeded to go through the initiation ceremony and took an oath, whilst touching a bible, swearing to support the brotherhood 23,

Dorset Agricultural Workers 1830’s

promising to never act in opposition to efforts supporting wages and assist in all lawful occasions to obtain fair remuneration for their labour.

In Victorian England, Landowners, the guardians of law and order could unite but union between labourers was not to be tolerated, especially, when their grievances were expressed in rioting crowds. James Frampton was very differential to people above his station, but below he never doubted his duty in controlling the masses. The ability to punish people who chose to create friendly societies is an example; he knew it was no longer an offence to be a union member, so he wrote a letter to the Government Home Secretary, Lord Melbourne for advice about controlling his minions.

In this letter, dated 30 January 1834, he states that secret societies between the Agricultural Labourers are being created and they are bound by secret oaths. These societies may unite and cause dangerous consequences to society if not controlled.

On the 31 January 1834 Frampton had a reply from Lord Melbourne’s Permanent Secretary J. M. Philips

This stated that:

Lord Melbourne thinks the Magistrates have acted wisely in employing trusty persons to endeavour to obtain information regarding the unlawful combinations which they believe to be forming along the labourers.

Lord Melbourne desires me to refer to the Mutiny Act of 1797 (for preventing taking or administering of unlawful oaths) which in cases of this description has been frequently resorted to with advantage. His Lordship thinks it is quite unnecessary to refer to Statutable provisions relative to the administration of Secret Oaths

Frampton feared that trade unionism threatened the power base and wealth of the landed upper classes. In 1792 whilst on the Grand Tour, a post university trip around Europe, with his half-brother Mr Charles Woolaston, he witnessed the French Revolution. He had also dined, in London, and paid respects to Charles X the former king of France who had attempted to bring about the destruction of citizens’ rights and caused the revolution of July 1830 that instigated a change to a constitutional monarchy.

On 2 August 1830, Charles X and his son the Dauphin abdicated their rights to the throne and departed for Great Britain.

The French Revolution (1789-1799) an insurrection of starving people was caused by the exceptionally hot summer of 1783, followed by long and harsh winters, resulting in crop failures. The crop failure may have been caused by erupting Icelandic volcanoes, later known as Laki. During the initial eruption in 1783 ash and gases entered the upper layers of the atmosphere, absorbed moisture and sunlight, changing the climate for years to come.

The Arrest of the Martyrs

On the 24 February 1834, Petty Constable Charles Brine left Dorchester Police Barracks at 4:00am to arrest the six martyrs before they had left for work. For his efforts he would be paid an extra four shillings (20p), a fifth of his annual salary. All six of the martyrs were shown the warrant for their arrest and willingly followed the Constable the seven miles to Dorchester. When they arrived they were escorted to Woolaston House, home of Mr Charles Woolaston, Chairman of the Quarter Sessions of the County of Dorset. After about ten minutes they were summoned by the constable to enter another room where Frampton and Woolaston were sat, the constable introduced the martyrs to them. Frampton asked the martyrs if they were aware that by asking those present at a meeting of the Friendly Society for Agricultural Labourers to take a secret oath, in an upper room at the home of the Standfield family on the 8 December, 1833, they were breaking the law. Frampton then turned towards the figure lurking in the shadows and asked him to step forward. It was Edward Legg, a Tolpuddle labourer who had asked to be admitted to the 8 December 1833 meeting of the Friendly Society. He was asked to identify the men gathered and asked if they were present at the union meeting, He said they were all present and Frampton rose from his seat and closed the meeting.

Constable Brine asked the men to follow him and when they asked what was going to happen next. Brine said with some regret “I’m afraid you’re going to prison” 23.

The Dorchester Trial

Dorchester prison was built in 1794, its capacity was 500 prisoners and from the iron gates at the front was a short walk to Woolaston’s home. Constable Brine handed the prisoners to John Cox the Turnkey awaiting at the prison gate. Inside the prison they were stripped of their clothes, their hair closely cropped and they were confined to a room where they remained for three days until the 27 February. Then they were sent to the Magistrate’s Court. Here James Frampton, Charles Woolaston, Henry Frampton, a group of local clergymen and Edward Legg were present. Legg was asked to identify the men and made a sworn statement that described the union initiation ceremony, this differed to the one made earlier, it was obvious that Legg had rehearsed a statement prepared by Frampton and Woolaston. The six martyrs were then fully committed to be tried at the next assizes.

They were then moved to a prison cell in the high gaol, where they slept on small straw beds laid on flagstones. They stayed there until the 15 March, then they were moved to the high gaol or Crown Court of the Shire Hall, here they were taken down to the dungeon. This consisted of six cells one side of a passageway and four on the other each side; their dimensions were 0.9 metres wide and 1.8 metres long, their bedding was straw scattered on the cell floor, no sanitation and the only heat in the cell block came from a fire in the gaolers room.

On the 15 March the Grand Jury were sworn in and it was unanimously agreed that the case be remitted for trial. The 22 members included local magistrates and landowners – all close contacts of Frampton who had briefed them in advance for the result they were expected to support. They were James Frampton his son Henry and Charles Woolaston, its foreman was William Ponsonby, the brother –in-law of Home-Secretary, Lord Melbourne. Other members were Henry Banks, Thomas Bower, Humphrey Weld, Benjamin Lester, John Michel, Thomas Horlock, John Bragge, William Banks, William Hanam, James Heming, John Lethbridge, Richard Stuart, Samuel Cox, John Hussey, George Loftus, James Fyler, George Thomson, Jacob Augustus and Thomas Badger. To provide testimony Frampton provided a few handpicked witnesses that had been rigorously rehearsed on what to say by Council for the Prosecution, Sir Edward Gambier.

Council for the martyrs defence, Mr George Butt submitted to the Grand Jury various written testimonies supporting the martyrs.

A farmer from Tolpuddle stated:

“The Loveless brothers were the last men in the parish that he should believe would been guilty of wrong.”

Mrs Susannah Northover, a farmer from William Morton Pitt’s estate, gave a glowing account of the industrious nature of the martyrs, stating:

Dorset Agricultural Workers 1830’s

“they have been agricultural labourers of mine for many years”…”They are all honest and industrious men”

The Rev. Dr Thomas Warren stated:

“he had known the martyrs for the last twenty years and they were honest, industrious, hard working men”

The testaments were handed to Judge Williams who cast them aside stating:

“He could not attend to them as they had not been handed in sooner”

Judge Williams was openly hostile to the defendants and informed the jury that Trades Unions and everything about them were evil.

Mr Butt stated that the defendants had been seeking only to provide a fund for workers to draw on in time of need.

The manacled prisoners were at the point brought up from the cells to stand before the Grand Jury.

They listened and spoke when asked, Lock and Legg took the stand and spoke about the initiation ceremony and the secret oath they took; John Cox, the Turnkey, mentioned that he had found a letter and a key on George Loveless; John Toomer, an employee of Frampton, received the key and went to the Loveless house and located a locked box, within the box were two books, one listed the names of the society members and the rules and regulations. The other book recorded members subscription paid and the amount. One of the rules stated that if masters attempted to reduce members’ wages they must leave their work and walk away in support of another member being discharged for being signed to the union.

The judge summed up the proceedings and stated the following:

“The object of all legal punishment is not altogether with the view of operating on the offenders themselves, it is also for the sake of offering an example and warning, and accordingly, the offence of which you have been convicted, after evidence that was perfectly satisfactory, the crime, to a conviction of which that evidence had led, is of that description that the security of the country and the maintenance of the laws on upholding of which the welfare of this country depends, make is necessary for me to pass on to you the sentence required by those laws.”

The jury retired and five minutes later returned with their verdict “guilty”. The prisoners were returned to their cells and waited 36 hours for their sentence.

On Wednesday 19 March the martyrs were paraded back to the court to hear their sentence. Judge Williams told them

… they had withdrawn themselves from the recognition of the law and kept their conduct private and secret from the rest of the world. I therefore state that you and each of you be transported to such places beyond the seas as His Majesty’s Council in their discretion shall see fit for the term of seven years.

When they returned to their cells George Loveless fell ill suffering from a chest infection caused by the insanitary prison cell and the acrid smoke from the fire in the dungeon; he was moved to the prison hospital 23.

Transportation to Botany Bay

On the 27 March, while George Loveless was still in hospital, the other martyrs, James Brine age 20, James Hammett age 22, Thomas Standfield age 44, John Standfield age 21 and James Loveless age 25, left the prison and boarded a coach to Portsmouth.

There they laboured on the convict hulks anchored in the harbour before boarding the transportation ship named the Surrey which weighed anchor on the 31 March with 200 convicts on board and sailed to Plymouth to collect a further sixty men before departing for Botany Bay, New South Wales, Australia on the 11 April. They arrived 100 days later on the 17 August 1834.

Back in London, in August 1834, there was civil unrest caused by the perceived illegal treatment of the Tolpuddle Puddle Martyrs. This resulted in the Grand National Consolidated Trade Unions’ mass demonstration from Copenhagen Fields, but this had no effect on politicians, apart from generating acres of newsprint distributed across the country.

Although, in June 1835, the new Home Secretary Lord John Russell sent a letter to the Governor of New South Wales and the Governor of Van Diemans Land (Tasmania) Australia granting a pardon to the six Martyrs, but they must stay at their location for the remainder of their sentence – the letters would have taken four months to arrive at their destination.

Another campaigner was Thomas Wakley, an MP and a medical man who had launched the Lancet. Within days of his arrival, on 27 May 1835, at Westminster he tabled a motion which stated:

‘if the Dorchester unionists were not pardoned and brought home, the working classes could expect no protection under the law as they had no vote and they were not represented in

Parliament where the laws were made.’

Even the great Reform Act had not given labourers the vote!

Dorset Agricultural Workers 1830’s

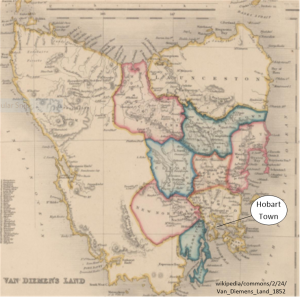

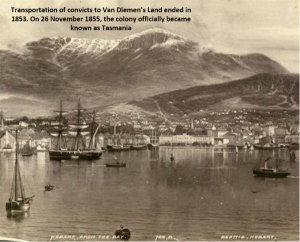

Transportation to Van Diemen’s Land

After his recovery George Loveless left the prison on the 5 April 1834, to board a stage coach to Portsmouth, the only seat available was on the coach roof, next to the luggage, exposed to the elements, with his leg irons secured to the coach. The journey to Portsmouth took about 10 hours, arriving at 9.00 p.m., he was then escorted to the convict hulk the York. He laboured on the hulk until the he was instructed that he would be moved to the convict ship the William Metcalf where he would be transported to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) Australia on the 25 May 1834.

The William Metcalf was carrying 241 convicts, each convict was allocated a small pillow and blanket, but the berth for six convicts was only 1.65 metres square – Loveless was only able to lay down for 28% of his confinement time, although he was allowed to go on deck for fresh air 4 hours a day. The journey took 111 days to sail the 15,226 miles from Portsmouth to Hobart Town the largest and most remote settlement in Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). The route taken was based on the Portuguese Trade route to the Spice Islands (Maluku Islands, Indonesia). On the 10 June, at 1,484 miles, they passed Madeira; 4 days later they anchored at Santa Cruz Tenerife and restocked the ship with fresh water and victuals; they then travelled 1,013 miles Cape Vere Islands; 11 days later the ship passed the equator and half way through the 2,940 mile journey to Rio de Janeiro and at Rio they restocked the ship with fresh water and victuals. Following the Portuguese trade route they went south and picked up the Westerlies, the Roaring Forties, where the waves were up to 24 metres high and continued on their 3,763 mile journey to the Cape of Good Hope. On the 25 August the ship dropped anchor in Table Bay, Cape Town, South Africa, where they restocked the ship.

On leaving Cape Town a strong southeast wind set up, knocking four days of their remaining 6,223 mile voyage to Van Diemen’s Land, they arrived on the 3 September 1834. The ship cruised along the coast providing the convicts a good view of the wooded terrain. The following morning the ship had entered Storm Bay and a favourable wind carried them 30 miles up the River Derwent to Hobart Town where it was taken to a mooring and dropped anchor at 10 a.m. The convicts stayed in their cells whilst government officials examined each convict, taking full particulars of their name, age, occupations and sentences; this description was entered into a large ledger 23.

The convicts stayed on board for another eight days. There were 248 convicts boarded in England but after the journey 40 convicts had died of a variety of illnesses, Scurvy, Cholera and other fevers, no doubt the effects of the unsanitary conditions. Their funeral comprised of a few words from the parson as their last farewell – no reading from the bible, no prayers, only a scribbled note of the day of death entered into the ships log, this would be included in a letter home to their families.

Disembarkation to the Penal Colony

At daybreak on the 12 September the convicts were told to go on the top deck to be landed and escorted to the prison barracks, here George Loveless was renamed Prisoner 848. He had an interview with the prison Governor regarding his trial at Dorchester followed the next day with interview with the local Assistant Police Magistrate Thomas Mason. At this meeting Mason stated:

“Well I have to tell you that you was ordered for severe punishment; you were to work in irons on the roads; but in consequence of the conversation you had with the governor yesterday, his mind is disposed in your favour; he won’t allow you to go where you was assigned; he intends to take you to work on his farm” 23.

Dorset Agricultural Workers 1830’s

Fortunately for Loveless, he only worked on the chain gang for one week and on 22 September he was sent to a government domain farm that provided fresh vegetables, milk and other produce to the residents of Hobart. It was very productive, the largest area under cultivation in Van Diemen’s Land and comprised on 120 acres, with 60 acres under crop, 153 head of cattle and 301 sheep. Loveless’s job was a stockman and shepherd, he lodged in one of the prisoner huts, but these were overcrowded. They had five beds with eight occupants, so consequently being the newcomer he did not have a bed until some of the older residents got into trouble and were ejected from the farm. This hut had poor roofing, when it rained the occupant got wet, made the bedding damp and aggravated rheumatic pains which were first brought on by cold irons round the legs since the 19th March.

Loveless continued working at the farm but was unhappy with the conditions and he wrote to the colony Governor. The letter enquired if it would be possible to be assigned to a master, but he received no reply. Later in November 1835, the Governor contacted the farm overseer, a man called Fitzpatrick, with enquires into Loveless’s character. Over the next two months the Governor enquired again, obviously to satisfy the criteria issued by Lord Russell in London. On the 29 December 1835 Loveless was summoned to the police station to answer a note received from the Chief Magistrate, Josiah Spode, wanting to know if he wanted his wife and children sent to the colony. Loveless stated: …how can I support my family when I am a prisoner. The Magistrate was annoyed by his response and threatened him with a flogging.

On the 24 January the colony Governor Arthur visited Loveless at the government farm and asked him to walk and talk about whether he would like to have his wife and children join him at the government’s expense. Loveless replied firmly that he would be a monster to send for his wife and have no way to support her. Arthur responded with “I have no doubt you will have your liberty as soon as your wife arrives”.

On the 27 January 1836 Loveless writes to his wife asking her to join him in Van Diemen’s Land and sends it, unsealed, to the Governor’s Office for approval. Nine days later he was informed by Governor Arthur to attend the police office, on arrival he was greeted by Spode who handed him an envelope. Inside was the following note:

“I am directed by his Excellency, the Governor, in accordance with His Majesty government, to give George Loveless (prisoner 848 from the William Metcalf) a ticket, exempting him from government labour to employ himself to his own advantage until further orders.”

23

Freedom for Loveless

As a free man Loveless had no money, without extra clothes, without friends and without a home. He was aware that the country side was populated with thugs, thieves and convicts. Where they would murder someone in ordered to be hanged and where lone children of ten were sentenced for stealing a handkerchief committed suicide as a way of escaping from the human predators that surrounded them. After a week he acquired a little employment providing funds to advertise his skills to a new prospective master.

His new employer Major William de Gillern, a German landowner who had served in the British Army, was situated in a new settlement called Richmond and lived at a farm called Glen Ayr. Richmond was an important military staging post and convict station linking Hobart with Port Arthur. Loveless received a wage paying job undertaking general farming duties and was accommodated in a stone built cottage. The Major became friendly with him and was impressed with his sense of duty, they even shared newspaper articles. One of these articles, written in a Van Dieman’s Newspaper dated September 1836, by Robert Murray remarked

“No doubt Governor Arthur has already sent George Loveless back home.” 23

Dorset Agricultural Workers 1830’s

On the 19 September Loveless wrote to Robert Murray to make further enquiries. He asked Murray if he would contact Governor Arthur and check the validity of his possible passage to England. A week later Major de Gillern received a letter from the Governor’s office asking that if Loveless was still working for him he should be informed that the Governor wanted to see him at Government House. This message was not passed on to Loveless. Loveless was eventually notified on the 8 Oct 1836 by Josiah Spode the Magistrate that he could have a passage home on the passenger and cargo ship Elphinistone, the same ship carrying Governor Arthur back to England. Loveless was unable to except this offer because he was still awaiting a reply from his wife concerning his request for her to join him in Van Diemen’s Land. This reply did not appear until 22 December 1836.

The Return Home

At the end of January 1837 Loveless received a letter from Josiah Spode the magistrate that informed him he was allowed free passage to England on the ship Eveline, with Captain Jamison, and berth in the crews quarters with steerage passengers allowances. He went to Hobart Town on the 29 January, 1837, to speak to the Captain to secure his passage and on the following day he boarded the ship at nine pm, the crew weighed anchor and the shipped docked at London on the 13 June 1837.

George Loveless’s colleagues imprisoned in Botany Bay were also granted a pardon in 1835 by Lord Russel, but they were unaware that they too would be able to return to England. George provided them the information required and they also were freed. They boarded a ship named John Barry in Sydney on 11 September 1837, but their return journey, via New Zealand to collect timber, was not paid for, they had to work their passage home. They arrived at Plymouth on the 17 March 1838, nine months after George Loveless 23

1830 Peveril Point, (2)Preventative Station, (3)Alpha Cottage, (4)Marine Villa and (5)Manor House Hotel

On 14th March 1836, the campaigner Thomas Wakley succeeded in his quest when the Government agreed that all the martyrs should have a full and free pardon.

On 25 April 1836 the London Dorchester Committee organised an official welcome home in London. The route was the same as for the Copenhagen Fields Rally the year before but in reverse. About 6,000 people turned out to witness the event, with five men taking the place of the martyrs, who were still in Australia, riding in an open carriage from Kennington Common to White Conduit House where a public dinner attended by over a 1,000 people was held. The guest of honour was Thomas Wakley, the dinner cost 2s 6d (12.5p) a head and was followed by a concert.

At the dinner, Wakley announced the launching of the Dorchester Labourers’ Farm Tribute, which was a plan to raise money to buy a farm for the Tolpuddle men. As a result, payment of a substantial deposit of £640 was made on leaseholds for seven years on two farms in Essex

James Hammett was the last to return home, arriving at the larger Essex farm, New House Farm, in August 1839. He was given a public welcome on 22 September at the Victoria Theatre – now known as the Old Vic. The reason why he did not return with the other four was because he had a criminal record, for metal theft, before his transportation and fell foul of the law in New South Wales. 23