The 74 Survivors

The assembled quarrymen, standing in the recent snow covering on a bitterly cold morning on the 6th January 1786, threw ropes over the cliff so that the survivors could be hauled up. They were able to help 40 ascend the cliff. Another 30 were washed away by the incoming tide as they awaited there turn to be hauled up.

The rescue team proceeded to assist the men who were still located 60 feet below, adjacent to Halsewell Rock, but located eight to ten feet inside the perpendicular cliff face that rose another 50 feet to the vantage point at the top. On the brink of the precipice two quarryman stood with rope tied around their waist and anchored to a bar fixed into the ground on the cliff top .

The Survivors

The only possible means of escape was to creep along the side of the cavern to the front and turn the corner where there was a narrow four-inch ledge and attempt to climb the perpendicular 100-foot cliff face. Some attempted to scale the cliff but were too weak from exhaustion and fell.

Although some were successful, the first man was the Cook, Robert Pierce, and James Thompson, a Quarter Master. The two of them spotted the nearest house and informed the remaining men below that they were going to get help 36.

The house was called Eastington, situated about a mile to the north east owned by Mr Thomas Garland, steward or agent to the proprietors of the Purbeck Quarries 36, immediately organised a team of workman and quarryman who procured ropes and hastily ran to the wreck site at Seacombe. They were followed by Garland and his friend the Reverend Morgan Jones who had been having breakfast with him 35.

They proceeded to the wreck site, where they were confronted with the scene of mountainous waves and fragments of ship timbers. In one place lay the ship’s rigging, wound up in sullen submission to the waves. In the rocks were a confused heap of boards, broken masts, chests, trunks and dead bodies huddled together. The entire sea scape, as far as the eye could see, there was the ship’s cargo comprising of carcasses, tables. chairs. casks and other debris that a ship carries 35.

The assembled quarrymen, standing in the recent snow covering on a bitterly cold morning on the 6th January 1786, threw ropes over the cliff so that the survivors could be hauled up. They were able to help 40 ascend the cliff. Another 30 were washed away by the incoming tide as they awaited there turn to be hauled up. On further investigation by Mr Garland another 20 were taking shelter in the large cavern about 30 feet from the bottom. At this juncture the quarrymen who were worn with fatigue, cold, wet and hungry were eager to get their share of two casks of spirit, which had just arrived 28.

After they had been refreshed, they proceeded to assist the men who were still located 60 feet below, but located eight to ten feet inside the perpendicular cliff face that rose another 50 feet to the vantage point at the top. On the brink of the precipice two quarryman stood with rope tied around their waist and anchored to a bar fixed into the ground on the cliff top.

A large cable was also anchored at the top and passed to the men standing on the edge, this cable had a loop which they lowered down to the cavern. Luckily the wind was blowing hard enough to force it under the projecting rock sufficiently so that the men could reach it. Whoever caught it put the noose around their waist and was pulled forward off the ledge, then swung out over the water and hauled up the cliff carefully 28.

They managed to haul up 18 survivors; they were all senseless and bruised but they recovered after being given brandy and gingerbread. Although three died before they could be assisted, 74 out of the total of 286 survived.

The route the survivors took to Eastington House was via a style that was later called “Black Man’s Gate” no doubt to signify the number of Indian crew members, Lascars, who were saved from certain death. Although, one Lascar died a few hours after he had been brought to Eastington House 28.

According to Henry Meriton the death toll was far higher than generally provided in recent text.

There were 39 officers, 50 seaman, 108 soldiers, one male passenger, eight female passengers, seven woman and 73 lascars this gives a total of 286. This figure cannot not be verified because the Ship’s Logbook has never been found 28.

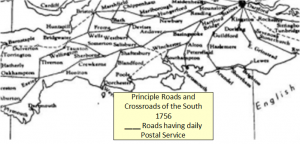

The next day 7 January 1786, Thomas Garland arranged and financed the senior surviving officers, Second and Third Mate Henry Meriton and John Rogers, journey to London so that they could report the loss of Halsewell to the HEIC Directors at India House 36. They were provided with two horses that they rode for 25 miles to Blandford Forum; this town was on the main route for the Royal Mail Coach between between Portland and Shaftesbury, at Shaftesbury they changed to the Exeter to London regular overnight Royal Mail Coach service 31.

As they stopped at Coaching Inns every 10 miles at towns on route, they also informed the local Magistrates that the rest of the survivors would be walking through their town soon, whilst on their long 120-mile march back to London.

The two officers arrived on the 8 January at noon 36.

There were a few sick survivors left behind and Thomas Garland ensured that they would be cared for

The remaining survivors left for London on Monday 9 January as they passed through Wareham the inhabitants provided food and refreshment. When they reached Blandford Forum the master of the Crown Inn, situated next to the River Stour, noticed the distressed seaman and invited them to his house where they had refreshment and a dinner, he presented each man with a crown coin (25p) to help them on their journey 36.

When the news arrived at India House the headquarters of the HEIC the Directors ordered handsome gratifications to the quarry-men and others who assisted in saving the survivors and provided immediate support for those out-lived. The quarry-men received the sum of one guinea a piece 36.

This is equivalent to over £80.60 today 48.

As for the financial loss to the HEIC, the Times newspaper stated that the loss did not exceed £6000, this represents the cargo only because the ship was owned by Captain Peirce’s father-in-law, Peter Esdaile who would bear the capital loss of the ship.