George Burt, Sheriff of London and Middlesex (1816-1894)

George Burt

George Burt (2 October 1816 – 18 April 1894) was a public-works contractor and businessman from Swanage, England, who managed the construction company Mowlem, founded by his uncle John Mowlem. George’s father was Robert (1788–1847), a stone merchant, whose stone and coal business was located in Swanage High Street. His mother was Letitia born Manwell (1786–1861), sister-in-law to John Mowlem who was working for Henry Westmacott, a well known sculptor-mason in London, at the time of George’s birth. George had five siblings, Elizabeth Letitia (1818–1889), Robert Henry (1821–1876), Charles (1823-?), Francis Alfred (1825-?) and Susannah Ann, ’Susy’ (1829–1871).

George grew up in Swanage, on the Isle of Purbeck in Dorset. In 1835, at the age of 19. George Burt moved to London to join Mowlem’s business, becoming a partner in 1844 and managing the business after Mowlem’s semi-retirement the following year. He married Elizabeth Hudson in 1841, and the couple had five children. Elizabeth Sophia (1843–1880), John Mowlem (1845–1894), Annie (1846–1918), Emma Rust (1849–1910) and George.

Upon taking over the Mowlem’s company, Burt substantially expanded the firm’s operations. In May 1851 the firm was ‘very successful’ in bidding for the London vestries’ contracts — some for only hundreds of pounds— that provided nearly all the firm’s work into the 1870s, earning it the nickname of London John. Work for ten major local authorities in the 1860s grossed an average of over £50,000 per annum. Surviving the lean years during the financial crisis of 1866-7, his company became a major public-works contractor and won the contract for Queen Victoria Street in the City of London (1869), followed by Billingsgate Market 7 (1874-7), and the City of London School in 1880 on the new Victoria Embankment, amongst others. In 1878, at the age of 62, he became the High Sheriff of London and Middlesex 5 .

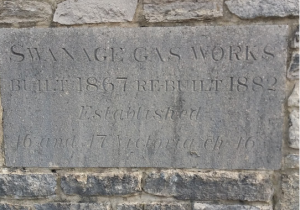

Burt, like his uncle, maintained an interest in Swanage, establishing a Gasworks (1867) and a Waterworks (1864), developing the Durlston estate, and lived in a large house called “Purbeck House”, now a hotel on the High Street. He and his wife bought the house for £550 and lived in it for 17 years. The porch is made of white Cornish granite, the mosaic floor is copied from the pavement in Queen Victoria Street, London and some of the tiles are from the Palace of Westminster.

The Gasworks was located near Prospect Farm on the current site of Victoria Avenue petrol station.

Before George Burt started constructing the first waterworks, the local population drew their water from wells or from springs situated at Court Hill, Mill Pond, Frog Well and Spring Hill. Some of these sources were contaminated by cesspits from buildings further up the hill. Burt wanted the residents of his new Durlston Park estate to have clean drinking water. So in 1864, he raised an Act of Parliament to supply Swanage with clean water from an artesian well 34.4 metres deep connected to a reservoir, 61 metres above sea level. The cistern was erected inside a stone tower at the top of Taunton Road, its turret similar to those at Durlston Castle.

In 1892, the town had expanded and required another source of water, this was found below the chalk at Ulwell. A well was sunk and a reservoir was constructed on the south of Ballard Down. To commemorate the event Burt erected a monument, an Obelisk, above the reservoir. This was another artefact that Burt had brought down from London as boat ballast – it was removed from St Mary Woolnoth at the junction of King William and Lombard street it was built between 1857-1875 5 .

In 1865, the Swanage suburb of Durlston was conceived and developed by Burt. However it was never completed, part of the land originally intended for the development is now Durlston Country Park. Although, Durlston Castle with the associated Stone Globe was completed in 1887.

He provided public access to the Tilly Whim caves but the access route had to be modified due to Sir J. C. Robinson’s ban on public access over his land, much to Burt’s consternation and annoyance – an example of their rivalry. George Burt resolved this issue, with a team of 20 workmen, created a steep stairway through the rock next to the coastal footpath, 30metres to the east of the caves. They used dynamite to blast a subterranean passageway that led to the mining lanes three metres below. This passage way was completed in 1887 10 .

The Castle has always been used as a restaurant of sorts, but in 1890 the upper floor was used briefly as a signal station by Lloyds of London. Between 1898 and 1900, the Nobel-prize winning physicist Marconi conducted early experiments in radiotelegraphy from the Castle to the Isle of Wight. In 1954 the Durlston Model Railway housed in the castle was described as ‘probably the most comprehensive display in the country

This bridge spans one of S. H. Beckles’ pits, a geologist who found that within a certain bed of the Middle Purbeck, provided an insight into the evolution of early mammals.

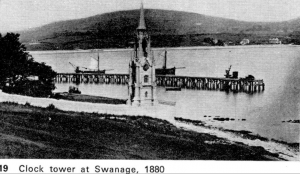

Many architecturally interesting buildings and monuments were scavenged as a result of the company’s construction work on prestigious projects in London and re-erected by Burt in Swanage and Durlston. For example the 1670 porch for the Mercers’ Hall now adorns Swanage town hall, a clock tower commemorating the Duke of Wellington which once stood at the Southwark end of London Bridge is now a feature of Swanage seafront and many of Swanage’s cast iron bollards were originally made for London boroughs, and still carry their names.

George Burt was buried at Kensal Green Cemetery. Control of the company passed to his descendants Sir John Mowlem Burt (1845–1918) and Sir George Mowlem Burt (1884–1964)

George Burt’s London Artifacts

In 1866 London , the Wellington Clock tower was deemed an unwarrantable obstruction by the Commissionaire of Metropolitan Police and was demolished by George Burt – the clock, made for the Great Exhibition of 1851, was returned to its owner a Mr Bennett of Blackheath London. Before the demolition, George Burt instructed his men to meticulously number the location of the bricks before the removal of the 1854 Wellington Clock tower that originally adorned the southern approach of London Bridge at a cost of £700 to the London borough and acquired free bricks as ballast for the Stone boat returning to Swanage.

After arrival at Swanage, George Burt reassembled it in 1868 at a cost of £1000, in the grounds of large seashore house called the Grove. Owned by Thomas Docra, a retired London building contractor who bought the property in 1866. In 1904, the spire was replaced by a Cupole because an adjacent owner of a residential property called Rockleigh objected to the ecclesiastical appearance of the spire; no doubt George Burt charged the owner a considerable sum by granting the owner’s wish. You can see why Burt was considered an entrepreneur 6 .

Sir John Charles Robinson CB FSA 1824 – 1913

Robinson was an art advisor to the Kensington Museum (later the V&A) and he became Queen Victoria’s surveyor of pictures from 1882 to 1901. Robinson acquired Newton Manor and transformed the house. At first Robinson and Burt were on friendly terms, but gradually as Robinson acquired more property they became bitter rivals.

Charles Edmund Newton-Robinson

John Charles Robinson had a son Charles Edmund Newton-Robinson, who was Educated at Trinity College and became British barrister, author, gemologist, fencer, and yachtsman

Born in London October 1853 and died in Swanage April 1913, wrote a book in 1882 about a visit he made to the Isle of Purbeck. The book was called “A Royal Warran: Or, picturesque Rambels in the Isle of Purbeck”.

A section describes his observations, in 1882, as he travelled from Newton Manor to the Royal Victoria Hotel.

Newton Manor

Belonged in the sixteenth century to a family of the name of Cockram, who also owned the estates of Whitecliff and Bucknoll. By the will of the last of the Cockrams, who died in 1830, Newton was directed to be sold, and through several intervening hands it passed to the present possessor John Charles Robinson.No vestiges of any very ancient building remain; the oldest part of the present house being the Elizabethan stone fireplace in the kitchen. The front, an excellent specimen of Purbeck stone and mason’s work, was built by Captain Cockram some sixty years ago; but the two drawing-rooms, one in Jacobean, and the other in a rather later style, were lately added; and the barn of the old homestead, with its open timber roof, was at the same time adapted to serve as a dining. hall. In this room is a fine carved stone chimney-piece, brought from a Florentine palace, and bearing the legend

IPA DIES QNQ.PARENS QNQ.NOVERCA. E: a hexameter, if the abbreviations are read aright, which is the equivalent of the English proverb, “Fire is a good servant, but a bad master.” 25 .

Prince Albert Memorial

Green meadows only divide Newton from the nearest extremity of Swanage, Courthill: so called from the adjacent estate, once the manor of Carrants Court. Here, if they have not been set straight again, we shall see the two upper courses of a little gray stone obelisk “to the memory of Albert the Good,” standing twisted across the lower ones by a blast of wind during the great snowstorm of January 17, 1881. That day will be long remembered at Swanage for the blinding, drifting wreaths, which filled the roads to the level of the hedge tops on either side, while the sea was driven a hundred yards up the main street of the town, and the deck of the pier washed clean away.Purbeck House

The residence of George Burt, Esq

Let us walk towards the sea, under the granite walls of Purbeck House, the edifice which stands so picturesquely in the midst of the High Street, dominating the scene from all sides with its machicolated tower, surmounting a host of tall chimneys and storied gable ends. Closely seen, the pink and blue granite chippings from Jersey and Aberdeen, laid with a regularity overcoming the cornery nature of the material, the smooth Portland stone quoins and dressings, the porch carved out entirely in solid grey granite, give an impression of the most finished workmanship, which does not yield to the sense of picturesque outline, until one retires to a distance. Then the case changes, and from every point of view the house becomes an interesting centre to the quaint, confused masses of dingy walls and roofs that straggle along the line of the street on either side. It occupies the site of an older mansion of less importance, at the back of which there had grown up a thickly-planted old-fashioned garden, such as in half-a-lifetime can hardly be reproduced. And this is the reason why, after old Purbeck House had fallen into decay, new Purbeck House rose up from the ruins on the self-same spot.

The architect was Mr. Crickmay of Weymouth

Perhaps some Londoners may recognise an old friend in the gilt flying fish performing the duties of a weathercock in an airy berth on the top of the tower, whence, Tantalus-like, he longingly surveys the blue sea, into which he never more can plunge again. This is a relic of old Billingsgate market, and is not by any means the only architectural importation to be found at Swanage Witness many instances to be described hereafter in their proper turn.

In a little sunken garden opposite Purbeck House, tenanted by one luxuriant evergreen oak, stands a cottage remarkable for nothing externally, but which many a Swanager would never forgive me for leaving without mention. A tablet in the gable informs the passer-by that this is “Wesley’s cottage;” Wesley’s, however, only because the religious reformer twice accepted a bed there. This, after all, is an association, if not a very interesting one, and very likely better authenticated than some others of greater pretensions. 25

Swanage Town Hall

Evidences are not wanting in this part of the High Street that the Swanage of the future will not be the mere jumble of plain, box-like dwellings that it has been in the past. The owner of Purbeck House has lately purchased and pulled down a cottage of two rooms, on the left-hand side of the way going towards the sea, the basement of which was sunk three or four feet below the level of the pavement, walking along which even a child could look straight into the first floor window! This palatial residence is now being replaced by an excellent specimen of a rich carved stone façade from a building of the time of Charles II., Mercer’s Hall, in London, which will stand in pleasant contrast to the well-proportioned but plain front of the adjacent shops in King Alfred Place. On these, by the way, the only elaborate ornaments are some capitals of wall-columns from the Castle of Mondolfo, in Italy, designed and executed in the finest style of the early Renaissance, with a delicacy, spirit, and variety which would make the fortune of a modern sculptor. Another set are to be seen lower down the street, on the other side, in the walls of a new shop called Exeter House.

Swanage Gaol

Down a dark and tortuous passage, or “drong.” as they are styled in Dorset, which formerly existed in rear of the cottage just mentioned as now no more, there used to lie, coyly hid, one of the sights of Swanage. Think of the terrible Bastile, conjure up recollections of all the tales of misery that hang about the Bridge of Sighs ; remember Chillon with its ghastly story, and call up to mind that dread inscription over the portal of the Inferno, “Abandon hope, all ye who enter here!” and you will still be very far from having a true conception of the prison-house of Swanage. Truly, a grim and dreary dungeon it was! Its vast proportions (twelve feet by eight), its stony cell unlit by the light of heaven, save through holes decayed in the nail-studded oaken door-were all eminently calculated to strike amazement into the beholder. And this sentiment, so rarely inspired by prisons, was apt to find vent in a burst of laughter when, after much difficulty, this mouldering inscription could be spelled out at last. “Erected for the Prevention of Wickedness and Vice by the Friends of Religion and Good Order.”Royal Victoria Hotel

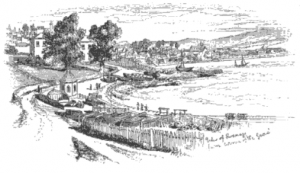

We are opposite the Royal Victoria Hotel, in which we need not doubt of securing a comfortable room, the first of August being still to come. This establishment, once the manor house of the estate now forming the new suburb of Swanage, stands nearly on the sea-level, with nothing but the road and a well-kept garden between it and the water’s edge. The centre is a good stone building in the Italian style, built in the last century, but rather overshadowed now by the large, plain wings built on by Mr. Morton Pitt of Encombe, nearly a hundred years ago, when he converted the mansion into an hotel, in emulation of Weymouth, then at the zenith of its fame as a watering-place. Mr. Morton Pitt, by the way, besides establishing the rope and twine factory at Kingston, encouraged new industries at Swanage also, in the shape of a herring-fishery and straw plait manufacture, the first of which has long since come to grief. Straw-plaiting, however, even now survives to be a little staple. In 1835, when the Queen (then Princess Victoria) visited Swanage, she was presented with an address and a bonnet of native manufacture; and at the present day Swanage straw goods are regularly sold in London. The hotel, it is to be feared, did not flourish in the days of Mr. Pitt, or even long after him. Many can remember it a dull woe-begone edifice, where you could have the very large coffee-room and a very small fire all to yourself as a sitting-room, if you liked, but nothing to eat except lobsters. Now things are changed, and certainly no one has any reason to complain of the lodging or the food. Securing ourselves against famine by ordering an early dinner, let us go out and see what is to be seen.Swanage Bay

Rather to one side in front of the hotel, a small sturdy stone pier with rounded ends and low parapet wall projects into the waters of the bay, and affords a convenient standpoint whence to obtain a general idea of the surrounding landscape. Before us the tranquil water lies, not ruffled by any breeze, closed in on all hands but one with a regular area of hilly land. Nearer, low green and reddish cliffs, dotted with a few small villas, and bordered with a fringe of bright yellow sands, on which a tiny village of red, blue, and white bathing machines has taken up a summer stand. Further, the horizon is excluded by that ubiquitous range of lofty green down, breaking away here into a grand white wall of chalk, terminated by the abrupt precipice of Bollard Head. So high these cliffs are, as to completely dwarf the bay, and to seem scarcely half-a-mile distant, although in reality a cannon shot from one of the old 18-pounders on the battery at Peveril Point would hardly reach them. Look more closely, and you will perceive some tiny bushes on the down-side. Those are great elms that have seen a hundred winters. That toy-boat under Bollard Head is a vessel of two hundred tons. In the far distance to the north-east, that thin and almost invisible grey line is the Hampshire coast, from Boscombe to Hengistbury Head; and still more to the eastward, those gleaming white specks are the Needles Cliffs, in the Isle of Wight. Our bay is quite lively in the calm weather; eight or ten sail of shapeless antiquated hookers are lying off at anchor, each on the top of a reflected image of itself, loading Purbeck stone from small walnut-like row barges, which take their cargoes from carts driven out into the shallow water till the wheel-axles and the horses’ bellies are submerged. The carts are themselves loaded from the great heaps of stone that constitute such an eyesore in front of the houses in the principal street, hard by on our left. A clumsy method of shipping this, but not really quite so wasteful as it looks. It was in full force in the days of J. M. W. Turner, the great painter, who, in a curious doggerel poetic effusion, jotted down in a notebook, perhaps, while he was making his well-known tour of the South Coast, harps on this very theme. “Even Swanage Bay can’t boast a pier,” is one of his rather unmusical lines. 25 .The Pier

Earlier in the present century, when men used to carry stone down from the quarries on their backs, it is probable that the employment of horses and carts for the sea-loading was as much a modern improvement as the carting from the quarries to the beach. Since Turner, too, the pier has sprung into existence; so there is hope for Swanage yet. The pier, par excellence, the wooden pier, built about 1860, is a rough, shambling timber jetty running out eastward into the bay more than a hundred yards, in continuation of a stone-built quay. It is generally the centre of a picturesque muddle of drying nets and lobster pots, fishermen, and more or less pallid passengers out of some noisy snorting Bournemouth paddle-boat, wrapped up in a cloud of its own smoke, and gay with bright bits of bunting. A stonehacker or two will be loading from the pier, and perhaps a coal cargo discharging there; and the roll of the maritime tenants of the bay is completed by a small fleet of graceful yachts that have folded their white wings here for the night. On their decks the crews are congregated about the forecastle, preparing an evening meal; and from one, the largest, are distinctly to be heard the dulcet strains of a fiddle and accordion, while a pet monkey is being chased screaming and chattering through the rigging 25 .

The Quarriers

Naturally, from the fact of the quarriers’ market being so restricted, it would be inferred that their weekly receipts must be very low. But this is not the case, as they really approach very nearly to those of urban artisans, although they waste much of their skilled powers by doing the work of labourers in getting and hauling the stone. Formerly, it is true, they were nearly all deep in debt to the merchants, as the result of a system of “truck” which practically banished money altogether from Swanage. Amusing stories are told of the curious exchanges this lack of coin made necessary, when bread was literally often given for a stone.

In spite of constant in-and-in breeding for centuries, the quarry-race often produces fine-looking intelligent men, and many pretty, dark brown-eyed children are to be seen at the cottage doors. The reasons why husbands or wives are seldom taken by the quarry people from outside their own kith and kin, are not far to seek. Ancient custom among them lays down the rule that no one can be employed in or about the working of stone unless the legitimate offspring of a quarryman and the daughter of a quarryman, and properly apprenticed to the craft. This and many other absurd restrictions are more or less rigidly kept in operation by the infliction of fines upon transgressors by a kind of trades’ union, the “Company of Marblers of the Island of Purbeck,” at the meetings of which the more intelligent men are generally outvoted, as in other and more important assemblies, by a large unenlightened majority. Other influences which keep the race to itself are their rough manners as compared with those of the upper classes of the townspeople, and their large earnings as compared with those of the labourers.

Then, again, the quarrymen seem to have distinct blood in their veins. Among them is to be found a great prevalence of surnames like Norman, Bonfield (Bonneville ?), Chinchen, Phippard, and others indicating a French origin; and when it is considered that many still extant churches, and the remains of other buildings of stone, date back to the earliest Norman times, it is not unreasonable to conjecture that the quarriers of Swanage are the descendants of a colony of Norman stone-workers 25 .