London Morning Chronicle, Labour and the Poor Swanage Survey 1850

The Swanage report was compiled by Charles Shirley Brooks, who was responsible for rural agriculture labour, the tin mining and fishing communities and small town industries – Swanage Quarries.

Swanage and the Isle of Purbeck Stone Quarriers

On the 18th October 1849, the Morning Chronicle, a leading Victorian newspaper, embarked on a social investigation of working class life in England and Wales. Set in the immediate context of concern over Chartism and the cholera epidemic, its intention was to provide a full and detailed description of the moral, intellectual, material and physical condition of the industrial poor.

The newspaper and the novel presented the only point of contact between the upper and middle class too the working class. They had read novels written by Charles Dickens that revealed the plight of the working class; this had generated public sympathy and a closer relationship between fiction and the plight of this class. The editor of the paper, Mayhew, proposed that these novels would supply a receptive audience for his paper if more detailed information, provided by a nationwide survey, about the working class was printed. For the first four months in the life of the survey covering the Labour and the Poor, two letters a week appeared from each of the correspondents. The Swanage report was compiled by Charles Shirley Brooks, who was responsible for rural agriculture labour, the tin mining and fishing communities and small town industries – Swanage Quarries 20.

An extract from a letter titled Swanage Quarries that was published in the London Morning Chronicle in a section named Labour and the Poor on 23rd January 1850

Letter XXVIII

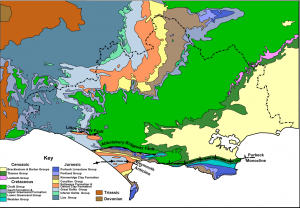

… Swanage has long been celebrated for its quarries and its quarriers. Almost from time immemorial stone has been extracted from the hills which sweep around the bay, until now the whole area, for miles back, is so perforated and undermined as to resemble one huge catacomb. From the earliest period, too, the quarriers have existed as an organised body-bound together, not only by the tie naturally created amongst those engaged in common pursuits, but also by a number of ancient and revered articles, which they have invariably treated as a charter of incorporation. Indeed, for centuries they were known in their corporate capacity as the Company of Marblers 20…

The quarry tenants, although paid more than farm workers, were limited to where they spent their wages. In 1850, during an interview with a reporter from the London Morning Chronicle a quarry man explained the antiquated payment system applied by the local stone merchants, for wrought stone delivered to the seafront for shipment.

Their pay was based on the amount of wrought stone they placed at a Stone Merchants store, known as a Banker. They generally earnt 15p/day, from this they had to finance the wage of a labourer and carriage charges transporting the stone to the Stone Banker, their money was paid by the Stone merchant as a credit note after the stone had been sold.

The order of credit enabled him and his labourer to purchase food and sundries from a shop owned by the merchant. If the quarry man wanted an item that was not available, for instance a pint of beer, he would purchase extra bread and use that as a currency at the local pub. When he bought the beer he would place the bread as a credit with the landlord, but he would pay a 20% transaction charge – bread 5d – beer credit 4d. Consequently, he had no coins of the realm and means to buy anything outside the closed community and at the mercy of the merchants raising prices when convenient to them.

This system of payment was considered unfair by the quarriers and the local dignitaries. At a meeting concerning the railway the Chairman stated that these men should be paid in the same manner as the clay miners at Corfe Castle. This was owned by Mr W. J. Pike of Wareham, who paid hard cash to his workers.

This payment by masters of their men’s wages wholly or in part with goods date from about the year 1464, this instance was an extreme case and a form of serfdom. The Truck Act (1887) an amendment to the Employer and Workmen Act 1875 which only excluded farm workers and domestic servants put a stop to this, the main object was to make the wages of workmen, i.e. the reward of labour, payable only in current coins of the realm and to prohibit whole or part payment of wages in food or drink or clothes or any other articles, but by 1887 the railway had arrived and the Stone bankers were superseded.

Extract from Letter XXVIII

Land Owner Levy

…The quarriers are now divided amongst themselves into two classes the master-quarriers, and the ordinary quarriers, who give their labour for hire…

When one or more intend to take a quarry, the first thing to be done is to obtain a lease from the lord…

…This is generally granted without much difficulty the lessees selecting their own ground, unless some good reasons exist for confining them in their choice. By the terms of the lease the landlord becomes, as it were, a partner in the adventure; his rent depending, as to amount, upon the quantity of stone yielded by the quarry. At Swanage the stone produced is generally of two kinds the solid block and the flat paving stone. The lord’s dues are regulated by the number of superficial feet excavated in the one case, and generally by the number of cubic feet excavated in the other. They amount to a shilling for every hundred superficial feet of paving, and the same for every hundred cubic feet of solid stone.

The landlord has thus an interest not only in the goodness of the quarry, but also in the industry of the quarriers. One of the conditions of the lease, therefore, is, that the quarry shall be worked a condition sometimes only complied with as regards its letter, when it is not the interest of the lessee or lessees either to work it constantly, or to give up the lease. It is seldom that anything in the shape of a written document passes between the parties, the leases having been verbal ones from time immemorial. And when a lease is once granted, the lessees cannot be dispossessed so long as they comply with the condition already alluded to.

As to the scene of operations, too, they are only limited as regards the shaft; but, having sunk the shaft at the point selected when the lease is granted, they are at liberty to work under ground in any direction they please, and as far as they please provided they do not transgress the bounds of the landlord’s property, nor come within a hundred feet of another quarry which is being then actually worked. If they go beyond the bounds within which it is competent for the landlord to licence them to work, and trespass upon another man’s land, the party thus aggrieved has his remedy, as in ordinary cases. If they go within the forbidden distance of another quarry, the parties whose rights are thus invaded look not for their remedy to the law of England, either common, statute, or ecclesiastical, but to the code peculiar to the locality, and which may be designated as Swanage Law….

Swanage Law: Trespasser Punishment

Extracts from Letter XXVIII

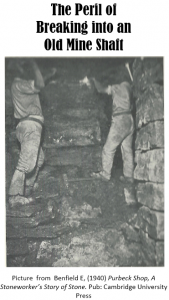

…For, amongst the other peculiarities of this singular district, it must be borne in mind that its people have their own code of laws, and their own mode of giving them effect. It is possible, no doubt, theoretically, that an English writ might issue into a Swanage quarry; but English law has, generally speaking, little to do with the practical administration of Swanage justice. When a party is suspected of trespassing in the manner alluded to upon the rights of his neighbours a meeting of the whole body is called, by whom the accusation is heard, and if a prima facie case is made out, a deputation is appointed to descend into the quarry and examine into the real state of the case. This deputation is not a mere committee of investigation, whose simple duty it is to inquire and report for it is contingently armed with administrative powers, which it is enjoined to put in force, should such a course be necessary, to do justice between the parties. Thus combining ministerial with judicial functions, the deputation descends into the quarry, provided with compasses and other appliances necessary for ascertaining the truth. If there is no ground for the accusation, the charge is dismissed, and the matter goes no further, unless the accusation be repeated; but if there is ground for it, and a trespass has actually been committed, a fine is imposed upon the delinquent party, according to the extent of his transgression.

If the trespass is one which is likely to be persevered in, it is the business of the deputation to take such steps as to render it impossible that it should be so. To effect this, it is armed with very summary powers, which it invariably exercises, whenever a necessity arises for putting them in force. The mode of proceeding in such a case is to destroy the portion of the quarry in which the offence is otherwise likely to be continued. This is done by breaking down the roof, or otherwise destroying the “lane” or level from which the stone is being excavated. When this process is not likely to answer the purpose, or when its execution might be attended with considerable risk or trouble, the end is more speedily affected by walling up the lane with mason work, and thus preventing the delinquent from having further ingress into it. It is seldom that the offence is repeated after this, at least in the same direction for the culprit is not certain that, should he again be caught trespassing in the same quarter, he himself might not be walled bodily in as a warning to others. So tenacious are the quarriers of the privileges which remain to them, that I am not sure that public opinion in Swanage would not sanction such a mode of procedure with one who should prove himself incorrigible in their infraction. One reason for enforcing the rule in question is that, if they approached nearer each other, they might mutually endanger the stability of their works, as will be seen when their mode of working is described… 20.

Stone Extraction

…The first practical operation is the sinking of the shaft, which is the only portion of the work requiring a little money capital on the part of the adventurer. The expenditure of this capital is, generally speaking, the best guarantee that the lord has that the quarry will be properly worked. The shaft is not sunk perpendicularly. as in most other mines, it being generally constructed at an angle of about forty-five degrees. It presents the appearance of a large hole in the form of a parallelogram, nearly perpendicular at one end, but slanting down at the other, at about the angle named. It is by the slant that access is had to the quarry, and the stone extracted is elevated to the surface. Along one side of this slant, or inclined plane, rude steps are constructed for the ascent and descent of the men. The rest of it is paved with flags, up which a truck is dragged with the stone which is being brought to the surface. Sometimes the motive power is a capstan-at others it is a horse. When the latter, the horse is, in some instance joint property, and does duty at more than one quarry. The depth of the shaft is regulated by that of the vein under the surface. There are three veins of stone lying parallel to, and at pretty regular distances, from each other. To reach the first vein, the shaft, according to circumstances, must be sunk for from forty to seventy feet. It is at the bottom of the shaft, when the vein is reached, and right under the perpendicular end of the shaft, that is to be found the real entrance to the quarry.

It looks precisely like what it is being neither more nor less than the entrance to an artificial cave. A horizontal passage is first driven from the foot of the inclined plane into the vein, from which “lanes” are struck off in different directions, in which lanes the quarry is worked. Generally, to get at the vein, a super incumbent stratus of solid but worthless stone has to be penetrated. Under this, and separated from it by only a very thin layer of clay, lies the first vein, in working which, the stone above forms a safe and substantial roof for the different lanes. They do not trust to it entirely, however, for as the lanes are widened, the roof is propped up by the rubbish which is accumulated.

Thus, if a lane is originally constructed above eight feet wide, it is never permitted to exceed that width, for. to the extent to which the solid mass is excavated on the one side of it, the roof is propped up by the rubbish on the other. In some places the vein is Six feet in depth, in which case it is all worked, when the men have sufficient room to stand at their labour. In others, however, it does not exceed three feet in thickness, when no more of the mass above or below is removed than is absolutely necessary to enable the men to work it. Thus, whilst some lanes are six feet high, others are not more than four, and the smaller the space, of course, the more laborious the occupation. Whenever they choose they can sink to the second or third veins. Many have gone to the second, but few to the third. Such as have done so have their shafts from 100 to 150 feet deep.

The stone is excavated with comparative ease, lying as it does in horizontal layers, in contact with each other, and having numerous perpendicular fractures, which enable the men to detach it in blocks of different sizes from the mass. If the layers are thin, the produce is paving instead of block stone. Most quarries produce both, whilst in some the layers are occasionally found so thin that a species of slate stone is extracted from them.

When the stone is dressed and ready for market, it is conveyed in waggons to the harbour. The farmers who lease the surface under which the quarries are worked, claim the right of carriage between them and the beach. This claim is acquiesced in, but the result is that the quarriers pay a much higher freight than they would otherwise do. If in any case the farmer should decline the carriage, the quarrier can then look where he pleases for his means of transport.

All the means and appliances of labour about the quarries are of the rudest description. Main force is the element principally relied upon, but little aid being derived from machinery. Long as the district about Swanage has been quarried, and immense as has been the quantity of stone shipped from it, it does not even to this day, possess a pier or jetty of any description. The vessels which receive the stone lie at anchor in the bay. The stone is dragged from the shore by very tall horses, in carts with very high wheels, as far into the sea as such an apparatus can venture with safety. From the carts it is consigned to the vessels, by means of barges, which are constantly plying to and fro 20.

Agriculture Workers

Agriculture Workers, especially after 1834, were paid considerably less than Stone Quarry labourers due to a dispute over their wages with a local landowner, James Frampton. The Tolpuddle Martyrs begged for a rise from their farmer from 35p a week to the Hampshire rate of 50p, the local landowner Frampton responded by lowering the weekly rate to 30p and the Bere Regis magistrate, James Frampton, sent the six martyrs on a 7 year working holiday in Australia. Their charge was holding a ceremony in which they swore loyalty to each other, known as “Administrating unlawful oaths”; this was based on an obscure law made 2 years before hand to deal with naval mutiny 21.

Rigged trial at Dorchester Assizes

The Tolpuddle Martyrs Museum states:…As the sun rose on 24th February 1834, Dorset farm labourer George Loveless set off to work, saying goodbye to his wife Betsy and their three children. They were not to meet alone again for three years, for as he left his cottage in the rural village of Tolpuddle, the 37-year-old was served with a warrant for his arrest..

Farm Labourer Exploitation,

The Tolpuddle Martyrs Museum states:… Between 1770 and 1830, enclosures changed the English rural landscape forever. Landowners annexed vast acreages, producing even greater wealth from the now familiar pattern of small hedged fields. Peasants no longer had plots to grow vegetables nor open commons for grazing their single cow or sheep and pigs.

- Average family expenditure (1840s)

- Rent 6p

- Bread 45p

- Tea 1p

- Potatoes 5p

- Sugar 1.5p

- Soap 1.5p

- Thread 1p

- Candles 1.5p

- Salt 2.5p

- Coal and wood 3p

- Butter 2p

- Cheese 1.5p

TOTAL 69.5p

Wages of 30p a week reduced families to starvation level unless they could be supplemented by working wives and children . 21

Farm Labourer Retaliation

Starting in the 1830’s the agricultural labourers formed a body called the Incendiares, people who intentionally start a fire with the purpose of causing damage or injury. The effect of riots in Hampshire, around Fordingbridge, was felt by 23 November 1830 on the Eastern chalk down land – in Cranborne, Edmondsham and Handley. But already an unpopular magistrate at Bere Regis, James Frampton (who later arrested the Tolpuddle martyrs), had to read the Riot Act at Winfrith, and had sermonised sullen crowds at Bere Regis, where a man and 2 boys were arrested. In Blackmore Vale, Dorset, not enough corn was grown to provide many labourers with work threshing, preparing the arable land in the winter.

Many were therefore forced to find parish work on the roads. If threshing machines were broken in the Vale, this was probably not so much because they caused unemployment, as because they symbolised impersonal power over the labourers. This generated a great deal of unrest in the farming community affecting 90% of the working male population and subjecting their families to starvation. At this time newspapers listed the fires nationwide, but later in 1850 they chose not to in fear of imitation by other groups of labourers.

There were attacks in the Isle of Purbeck at Samuel Townsend’s Brewery, in Pound Lane, Wareham in 2 March 1836. Both the Brewery and attached cottage were both totally destroyed. Three days before this incident an arsonist destroyed the property of Reverend N Bond of Rushton Farm, Wareham. A Wheat Rick and barn were totally destroyed and there was a further instance of a barn fire at Arne, which was blamed on a natural occurrence to quell the masses 22.

Agriculture Workers

Agriculture Workers, especially after 1834, were paid considerably less than Stone Quarry labourers due to a dispute over their wages with a local landowner, James Frampton. The Tolpuddle Martyrs begged for a rise from their farmer from 35p a week to the Hampshire rate of 50p, the local landowner Frampton responded by lowering the weekly rate to 30p and the Bere Regis magistrate, James Frampton, sent the six martyrs on a 7 year working holiday in Australia. Their charge was holding a ceremony in which they swore loyalty to each other, known as “Administrating unlawful oaths”; this was based on an obscure law made 2 years before hand to deal with naval mutiny 21.

Rigged trial at Dorchester Assizes

The Tolpuddle Martyrs Museum states:…As the sun rose on 24th February 1834, Dorset farm labourer George Loveless set off to work, saying goodbye to his wife Betsy and their three children. They were not to meet alone again for three years, for as he left his cottage in the rural village of Tolpuddle, the 37-year-old was served with a warrant for his arrest..

Farm Labourer Exploitation,

The Tolpuddle Martyrs Museum states:… Between 1770 and 1830, enclosures changed the English rural landscape forever. Landowners annexed vast acreages, producing even greater wealth from the now familiar pattern of small hedged fields. Peasants no longer had plots to grow vegetables nor open commons for grazing their single cow or sheep and pigs.

- Average family expenditure (1840s)

- Rent 6p

- Bread 45p

- Tea 1p

- Potatoes 5p

- Sugar 1.5p

- Soap 1.5p

- Thread 1p

- Candles 1.5p

- Salt 2.5p

- Coal and wood 3p

- Butter 2p

- Cheese 1.5p

TOTAL 69.5p

Wages of 30p a week reduced families to starvation level unless they could be supplemented by working wives and children . 21

Farm Labourer Retaliation

Starting in the 1830’s the agricultural labourers formed a body called the Incendiares, people who intentionally start a fire with the purpose of causing damage or injury. The effect of riots in Hampshire, around Fordingbridge, was felt by 23 November 1830 on the Eastern chalk down land – in Cranborne, Edmondsham and Handley. But already an unpopular magistrate at Bere Regis, James Frampton (who later arrested the Tolpuddle martyrs), had to read the Riot Act at Winfrith, and had sermonised sullen crowds at Bere Regis, where a man and 2 boys were arrested. In Blackmore Vale, Dorset, not enough corn was grown to provide many labourers with work threshing, preparing the arable land in the winter.

Many were therefore forced to find parish work on the roads. If threshing machines were broken in the Vale, this was probably not so much because they caused unemployment, as because they symbolised impersonal power over the labourers. This generated a great deal of unrest in the farming community affecting 90% of the working male population and subjecting their families to starvation. At this time newspapers listed the fires nationwide, but later in 1850 they chose not to in fear of imitation by other groups of labourers.

There were attacks in the Isle of Purbeck at Samuel Townsend’s Brewery, in Pound Lane, Wareham in 2 March 1836. Both the Brewery and attached cottage were both totally destroyed. Three days before this incident an arsonist destroyed the property of Reverend N Bond of Rushton Farm, Wareham. A Wheat Rick and barn were totally destroyed and there was a further instance of a barn fire at Arne, which was blamed on a natural occurrence to quell the masses 22.